Distance Deepmind Research Scientist Felix Hill It's been close to two months since he last spoke out on the X platform.

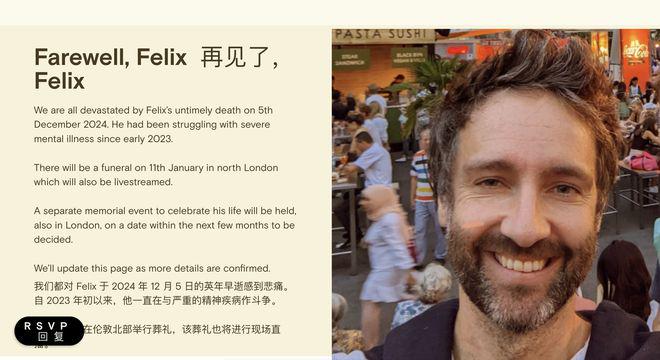

Unfortunately, the research scientist sadly passed away on December 5th of last year due to a long battle with severe mental illness.

And the news was confirmed by Douwe Kiela, an adjunct professor at Stanford University and CEO of Contextual AI, at X Platforms.

After the news broke, many in the AI community took to Douwe Kiela's comments section to remember his friend.

Even Gary Marcus, who has had academic disagreements with Felix, said:

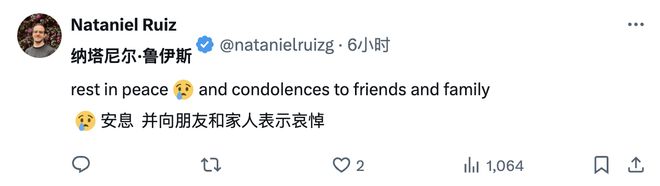

David Ding, CEO and co-founder of Udio, Nataniel Ruiz, senior research scientist at Google, and a number of research scientists at Meta and OpenAI have also posted messages of condolence.

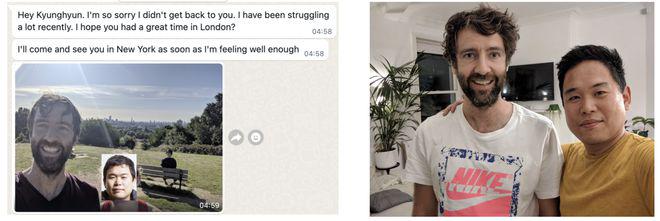

Kyunghyun Cho, a renowned AI researcher and professor at New York University, met Felix in Montreal in the summer of 2014, and has since posted a reminiscence. At the time, Kyunghyun was a postdoc and Felix was a visiting student.

They became close friends over an academic discussion about grammatical structures.

One of the things they achieved after conducting research work together was to create the trend of 'huge tables' in papers published in 2016, a style that has been widely emulated by academics in the 3-5 years since.

The man is gone, but Felix Hill left a legacy of ideas that will live on.

Even unseen peers were impressed. Jim Fan, Senior Research Scientist at NVIDIA, also took to the X platform today to re-post Felix Hill's blog and to honor his friend's memory.

He led an AI research team, but couldn't overcome his own inner demons.

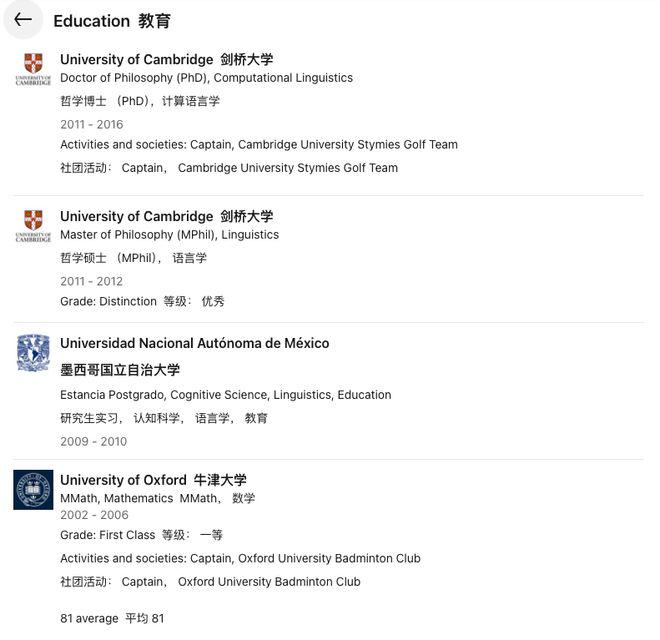

Linkedin's public profile shows that Felix Hill was a good student with good grades in the secular sense.

His undergraduate degree is in Mathematics from the University of Oxford, where he also captained the Oxford badminton team. His postgraduate internship was at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where he specialized in cognitive science, linguistics and education, focusing on interdisciplinary areas (cognitive science and linguistics).

This experience not only enriched his international perspective but also broadened his academic interests.

He studied Linguistics and Computational Linguistics at the University of Cambridge from 2011-2016, where he also captained the golf team.

Felix's career has been going well since he entered the workforce.

He has been involved in education as a math teacher for 14 months, preparing 14-18 year olds for exams and university applications, and as a philanthropist, supporting local education NGOs.

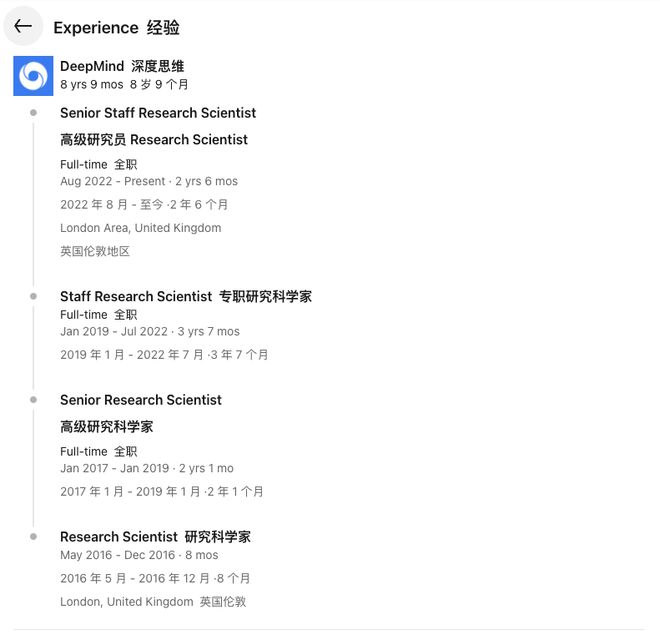

Felix had a long career at Google Deepmind after 2016.

Prior to his death, he led a team at Deepmind that studied the interaction of language and general intelligence. At the same time, he began to shift his focus to cutting-edge technology research, specializing in linguistics, machine learning, and AI model development.

Google Scholar data shows that its papers have a total of 19,680 citations with an h-index of 42, including a higher 16,608 citations after 2020, which has a wide impact on related fields.

At Platform X, the friend wrote in his introduction:

However, the AI research scientist, who has been a huge success in the eyes of the world, has been struggling with a serious mental illness. In Felix's blog, he also chronicles the final stages of his life:

In April 2023, his mother died of Alzheimer's disease, and during the same period he was hospitalized for acute psychosis, possibly stress-induced. The following 12 months were characterized by extreme anxiety and deep depression.

After receiving understanding and support from her employer, including therapeutic support and spiritual care, and starting to get better after a 6-month period of life-threatening depression, she began to think about and record her observations and understanding of stress and anxiety.

However, fate is often cruel. On December 5 of last year, this friend ended up passing away too soon.

R.I.P.️

Attached is Jim Fan's retweet of Felix Hill's original blog post.

Responsibility for 200 billion weights

The Stress of Modern AI Work

By Felix Hill, October 2024

Over the past two years, the AI field has changed irreversibly.

ChatGPT has close to 200 million monthly active users, and Gemini had close to 320 million visits in May 2024. Today, AI enthusiasts can even use AI microwave ovens, AI toothbrushes, and even AI soccer balls.

However, for many of us working in AI, this surge in popular interest has been both a blessing and a burden. It's true that paychecks have risen, as have stock prices and market valuations. But at the same time, this change has brought with it a unique kind of stress.

This blog is about the pressures that modern AI brings. It is aimed at an audience of those working with AI (which is conservatively estimated to be about 87% of the world's population), and in particular those working on AI research.

Ultimately, I hope that by discussing the stressful elements of AI research, I can make life a little more enjoyable for those fortunate enough to work in this field. Because despite the current chaos, it's still a wonderful and fulfilling career; one that has the potential to answer many of the great questions of science, philosophy, and even humanity itself.

escape from nowhere

A few months ago, I attended a friend's 40th birthday party. We're close friends, so I knew quite a few of the guests at the party, and some of them were very familiar. But there were also some people I didn't recognize at all.

Among those I don't know very well, I've noticed a strange phenomenon.

Despite the fact that I wasn't very well (I'll get to that later) and obviously didn't really want to initiate a conversation, there was a small line of people around me just because people knew I was in the DeepMind work, a lot of people want to talk to me.

These conversations weren't about relaxing topics like soccer or 80's music, but about the one topic I'd most like to avoid: AI. While I was flattered by the interest in my work, it also made me realize how much has changed in the last two years. Bankers, lawyers, doctors, and management consultants all wanted my thoughts on ChatGPT; and while very few of them use these LLMs directly in their work, they're all convinced that AI is changing in some important ways that they need to know about.

As a researcher, I'm sure you can understand the feeling of not being able to 'turn off the switch' in social situations.

But things got worse. Even in my own home, I couldn't escape.

I stopped watching the news a long time ago for fear of triggering anxiety. But even when watching soccer, VH1, Inspector Montalbano, or that wonderful TV adaptation of the Neapolitan Quadrilogy, the commercials are full of references to AI.

In the interim, I've often thought about packing my bags, traveling across the continent, and joining a reclusive religious community. Though I wouldn't be surprised that even Vipassana yoga may now be infiltrated by AI to some extent.

implied competition

Several large companies seem to be competing to develop the largest and most powerful large-scale language models, which in itself creates enormous pressure; no matter which company you work for.

In current AI research, it can sometimes feel like you're engaged in a war. From Adolf Hitler to Holland Schultz, we know that engaging in war can lead to serious consequences, including mental illness, divorce, and suicide.

Of course, this is not to equate participation in AI research with physical combat in a 'real war'. But from my own experience, the similarities between the two, while slightly far-fetched, are real.

Impacting the company's bottom line

Typically, researchers engaged in industrial research are not accustomed to the idea that their work has a direct and immediate impact on their employer's bottom line.

Of course, many researchers dream of such an opportunity. But in the past this has usually only happened once a decade.

Today, the results of basic research on the LLM typically lead to only subtle, short-term fluctuations in model performance. However, these fluctuations can, in turn, lead to multi-billion dollar fluctuations in stock prices due to the high level of public interest in LLM performance.

This dynamic is clearly very stressful, and it's not something that AI researchers are trained to deal with in graduate school, postdocs, or even in their work until 2022.

Money, money, money.

Most AI researchers, especially those over a certain age, don't do research for the sake of making money in the first place. Making a ton of money for a job you love may sound like good medicine, but it can also trigger strong feelings of anxiety. This is especially true when the external factors that drive the increase in income are out of their control, or when these factors make their love for the job diminish.

Whether AI-related or not, there's plenty of evidence to suggest that the sudden accumulation of wealth can lead to all sorts of problems; one need only look at actors or singers who, after years of hard work, finally become an overnight sensation. Addictions, broken relationships, shattered friendships, and even suicide are some of the more common consequences. These are issues that I personally know all too well.

Scientists have no place.

The scale, simplicity, and efficiency of LLM make it difficult for scientific research to become 'relevant', i.e., it is difficult to directly help improve the performance of LLM.

Many top LLM researchers have begun to espouse Rich Sutton's "bitter lesson" that little innovation is needed beyond scaling.

Even if the theoretical possibility of making substantial innovations exists (and it undoubtedly does), realizing these innovations often requires the repeated training of the largest LLMs under varying conditions.This is something that even the largest companies can hardly afford at present. For an 'average' research scientist, this situation can be exhausting.

These conditions are already severe for industrial scientists who are used to working in small teams (5-10 people). And for PhDs, postdocs, and AI/CS/ML faculty in academia, the pressure is undoubtedly even more intense.

Published Papers

While researchers in academia can (and should) continue to publish the insights they gain from LLM experiments, it is becoming increasingly uncertain for scientists in industry whether publication remains a viable outcome of research.

Getting published has long been a central part of the scientific process and a key tenet of AI research. Most AI researchers I've talked to, especially research scientists, agree that publishing papers is an integral part of our careers.

However, at least in industry, the publication of research results as a viable option has become increasingly uncertain over the past two years. Even small tricks that can marginally improve the performance of LLM can become critical 'weapons' in the LLM war. Whether or not these 'secrets' should be made public, and whether or not this benefits the organizations that fund the research, is always a delicate issue.

All of this means that researchers often have no control over the fate of their ideas. And, for me at least, this situation can trigger a great deal of stress.

Startups

Of course, one possible way to escape from these concerns is to form a scientific vision, raise money, and create a startup. Indeed, the current proliferation of AI startups (large and small) suggests that many scientists have already chosen this path.

However, becoming a founder doesn't guarantee that you'll be free of stress-related problems. In fact, the path is known for its high stress. Many well-funded AI startups fail, even in the current climate of investor enthusiasm. From my own experience, being a founder can be a particularly lonely journey. It's certainly a viable option for aspiring scientists today, but it doesn't make scientific research any easier or less stressful.

Why did I choose to write a blog about stress?

The last two years have been chaotic and crazy for the AI world, and also a particularly tumultuous time for me personally.

In April 2023, my mother died after a long battle with Alzheimer's disease. And at that time, I was hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital for acute psychosis, and stress was likely a major precipitating factor in all of this. For the next 12 months, I was theoretically recovering, but in reality was in a constant state of extreme anxiety and deep depression. During this time I was very fortunate to have employers who understood my situation (and recognized the value of my contribution to the company) and who provided me with ongoing therapeutic support and ethical care.

After another 6 months of life-threatening depression, I'm finally starting to feel better and have recently felt empowered to write about my experiences. I've come to realize that stress and anxiety have always gone hand in hand; in fact, they may be essentially the same thing. Of course, like any adaptive trait, anxiety can be beneficial to a certain extent (it can boost productivity, for example), but when it becomes malignant, the consequences can be dire.

It is in reflecting on my experiences in AI over the past two years while trying to relearn how to be an AI researcher that I have gained the insights I share in this blog. Of course, just sharing these insights won't solve everything, but one of the only things that gave me hope in my darkest moments was knowing that I wasn't alone. If you are in pain right now, trust me - you are not alone.

social anxiety

I've already discussed many of the reasons that might make people currently working in AI research feel stressed or anxious. But there is another form of stress that I haven't yet mentioned because I've been lucky enough to never experience it myself. That stress is social anxiety.

According to friends, those with social anxiety can find group interactions challenging. Such difficulties are particularly acute in the modern world of AI, where large project teams and cross-continental collaboration have become essential. Today's high turnover rates in the industry only exacerbate the problem, as established teams (often seen as a social 'safety net') can be destroyed overnight. Frequent turnover can also lead to trust issues, as once-reliable allies may join 'hostile' research teams.

The good news is that, as with all the manifestations of anxiety or stress I've discussed before, social anxiety can be overcome. The process of overcoming it begins with cultivating natural support networks, such as relying on family and friends in 'non-AI' fields. But the critical second step is for all of us working in AI to begin and continue to have honest conversations about stress.

So please share your experiences via tweet or comment. Let's work together to make AI research not just a vibrant, intellectually challenging place, but a field of compassion and goodwill.